Everyone hurts at the pump, even gas stations

Alex Kinnier

Market forces like supply chain issues, labor shortages, and war are colliding to drive gas prices up, and there is an important, ongoing conversation about whether fuel retailers can alleviate the pressure on consumers by reducing markups at the pump.

Right now fuel retailers are just trying to sustain their businesses, not grow them. Asking fuel retailers to reduce sign prices is asking them to sacrifice their business.

The retail fuels industry goes through regular high and low margin periods. It’s the way the market balances itself. Yes, there are times when fuel retailers benefit from a higher-margin environment. But those times are critical to recoup their losses from lower (or negative) profit margin times.

Today as sign prices reach $5.00 per gallon in some places, consumers want to know if that means fuel retailers are making record-high profits.

The data shows they’re not.

Margins are not abnormally high right now, and as the oil market steadies, sign prices will go down.

Margin volatility makes artificially lowering sign prices dangerous for businesses.

A common misconception about gas stations is that they’re all owned by big corporations that can sustain big losses. In reality, half of them are small businesses, called “independent dealers,” and they’re at the mercy of the market. These retailers are reliant on daily profit margins, and these margins are famously thin. The Energy Information Administration breaks down all the costs that go into pumping a gallon of gas:

“Distribution & Marketing” has two components: (1) what the gas station earns as a business, and (2) what the fuel distributor earns for their work to transport and deliver the gasoline. Combined, this only makes up 5-17% of the total price of gas. In Zachary Crockett's recent article, he explained that when you factor in costs like labor, utilities, insurance, and credit card transaction fees, gas retailers receive a fraction of the price listed on the sign: to the tune of $0.03-$0.07 net profit per gallon. This puts the net profit margin of a gas station at less than 2%. For reference, the banking industry has roughly 30% net profit margins.

Retail fuel sales is a tough business. To oversimplify, a retailer’s margin isn’t really up to them. Retailers buy a “jobber” of fuel—the round trucks we see on the road delivering gasoline—at a wholesale price, and their sign price is fairly out of their control because they have to price competitively against the station down the road. That same competition makes it so that when the market moves, they may have to sell at a loss for some time instead of immediately changing their sign price. Otherwise customers will just go to the nearest gas station with a better price.

As a result, the retail fuels market operates in regular cycles of low and high margin periods.

They lose money, and then need to earn it back when the market allows. Without those earning periods, these businesses are at risk.

Let’s look into Upside’s data to see what these cycles look like.

Getting back to average

We analyzed the weekly rolling average profit margin at stations across the country to see when margins are above or below average, and by how much.

Looking back 12 months at thousands of gas stations nationwide, we determined the average profit margin. In that period, there were cases when margins were so thin that retailers were selling at a loss.

%2520Compared%2520to%2520Historical%2520Average.png)

Over the last few months as the cost of oil drops, margins are expanding and are up by roughly the same amount they were down in the last year. This allows retailers to recoup their losses, pay their bills from prior months, and break even year-over-year.

The question is whether the current margin highs are abnormally high— and whether the record-high gas prices we see on the road today signify that fuel retailers are making record-high profits.

They’re not.

Let’s look back to 2020 for a recent example:

%2520Compared%2520to%2520Historical%2520Average.png)

January to June 2020 followed the highs and lows we expect in the industry.

When COVID-19 response measures took hold across the United States in March 2020, net profit margins rose to extremely high levels. Demand cratered because consumers were in lockdown, and fuel retailers across the country had to increase sign price to cover fixed costs like utilities and rent. Then margins went negative.

The net margin highs between March and June 2020—which was roughly 17% above average over the whole period but got up to 22% above average—is more than double the margins that fuel retailers are experiencing right now in 2022 over the same period (up 6%, with a 14% high).

So right now in July 2022, net margins are not abnormally high, and retailers are operating the way they need to operate so they can maintain their businesses.

As soon as the market equilibrates, margins will come back down to average and sign price will follow. That trend would only be disrupted if we either of two things happen: there is a significant reduction in consumers’ demand for fuel (brought on by something like a deep recession), or there is a change in refiners’ capacity (brought on by something like an end to Russia’s war in Ukraine).

In this highly competitive industry, it’s not in a fuel retailer’s interest to keep sign prices high.

The typical U.S. fuel retailer has at least one competitive gas station only 0.016 miles away, and at least 1.5 stations within a half-mile radius. Not only do consumers have a lot of choices when it is time to fill-up, but they are purchasing less gasoline than they were a year ago. People are driving less because of record-high sign prices, resulting in 4% less gasoline being sold on average per gas station compared to last year.

When the wholesale price for gas increases, gas stations either need to raise their sign prices or deal with lower margins. Stations often wait as long as they can before they raise prices, because they could potentially lose customers to nearby gas stations with a lower price.

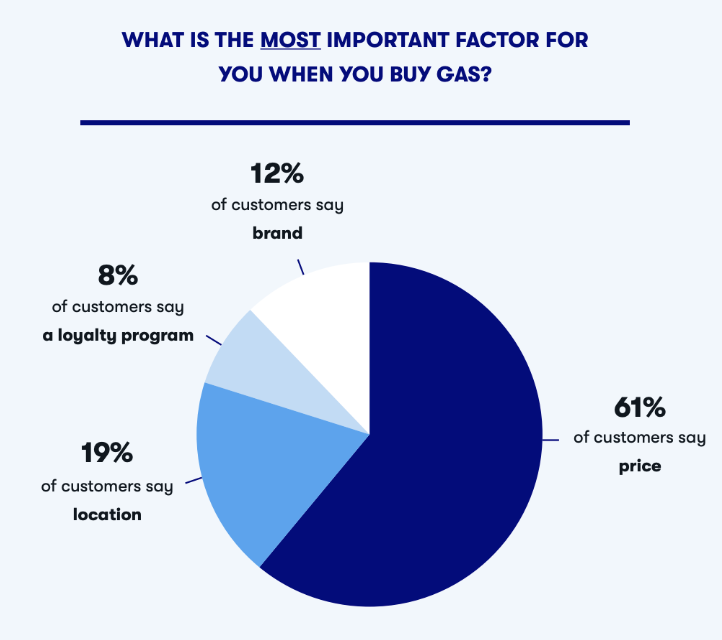

We surveyed 1,300 consumers to understand what factors motivate them to buy gas and the two most important factors are sign price and location. This insight is something we see time and time again across various surveys, and retailers know this to be true. So it is not in their economic interest to raise their sign price if they want to attract customers and ensure that they are able to sell all of the gas in their pumps.

In 2022, most retailers aren’t being greedy, they are trying to sustain their business. When it comes to alleviating inflationary pressures brought on by the fuel sector, artificially lowering sign price is not the lever that will do the most good.

Share this article:

As co-founder and CEO of Upside, Alex Kinnier is working to transform brick-and-mortar commerce. His success in growing Upside into a company driving $6B+ in commerce annually was informed by his years of experience leading product development teams at Opower, Google, and Procter & Gamble. Outside the office, Alex is an ardent technologist and investor, always on the cutting edge of products with the potential to change the world.

Request a demo

Request a demo of our platform with no obligation. Our team of industry experts will reach out to learn more about your unique business needs.

.png)